By Todd D. Jones, MAI, CRE, FRICS, and Michael J. Mard, CPA/ABV, CPCU

At the end of 2017, The Walt Disney Company filed an Agreement and Plan of Merger with the Securities and Exchange Commission to merge with Twenty-First Century Fox, Inc. and related entities. Disney offered some $52 billion for the deal, so it really feels like Disney bought Fox [2]. The deal will be a boon to Disney [3]:

The House of Mouse, which is a home to Lucasfilm (the “Star Wars” movies), Marvel (the “Avengers”) and Pixar (“Toy Story”) as well as the Disney brands, will own Fox’s film production businesses including Twentieth Century Fox, Fox Searchlight and Fox 2000. This would bring the “X-Men”, “Fantastic Four” and “Deadpool” rights back into the Marvel fold and add “Avatar” — the highest grossing movie in history — to Disney’s family of franchises.

Additionally, Disney will acquire the Fox film studio with hit TV series including This Is Us, Modern Family, and The Simpsons, regional sports networks and entertainment cable channels like National Geographic, FX Networks, Fox Sports Regional Networks, as well as international networks like Star India, a controlling stake in Hulu, and a 39% stake of European satellite provider Sky.

But wait, where’s the dirt? All of these assets are, well, imaginary; even the satellite doesn’t sit on dirt! A quick search of the government data base shows Disney will acquire over three million Fox trademarks. For $52 billion. How can this be? Do income producing properties have an intangible asset income producing component? Should such considerations always be measured and allocated in a value in exchange premise?

The purpose of this article is to prove that the income and return relationship to value (IRV) applies to all assets, tangible and intangible. This income and return relationship to value when properly applied to an array of assets, tangible and intangible, will convey economically viable returns whose average weight sum to a viable weighted average cost of capital which reconciles to the band of investment. Put differently, the value of a subject’s real property should be consistent whether the premise is value in use or value in exchange.

It is a fundamental axiom enshrined in The Appraisal of Real Estate, 14th edition that:

A $ return divided by a respective rate of return = value for the asset (I/R = V, or IRV)

If this is true, then:

A $ return divided by a respective rate of return = value for an intangible asset

Further:

A $ return divided by value = a respective rate of return

And:

A respective rate of return times value = $ return

Of course if the property has multiple assets, say, cash, personal property, leasehold interest, real property, then each asset will have a separate and distinct return. For instance, the return on cash might be 2% in today’s environment. Unquestionably, the weighted average of all of the property’s returns will equal the weighted average return for the property as a whole.

It follows that the value of real property can be expressed as a function of the total value of the income producing property (its business enterprise value) less each of the component asset values of that enterprise. The sum total of the returns weighted by value will equal the overall weighted average cost of capital for the business enterprise value.

This weighted average return on assets is mathematical and applies whether the premise is value in use or value in exchange. That is, when all assets, tangible and intangible, are properly segregated, the value of the real property will not change based on the premise. The rest of this article and the appendices will prove this claim with all of the authority of the Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice, the American Institute of CPA’s Statement on Standard for Valuation Services, the Internal Revenue Service, the Securities and Exchange Commission and numerous courts, circuit, district, tax and US Supreme Court.

What are intangible assets?

The Report of the Brookings Task Force on Intangibles (Brookings Task Force) defined intangibles as[5]:

… nonphysical factors that contribute to or are used in producing goods or providing services, or that are expected to generate future productive benefits for the individuals or firms that control the use of those factors.The International Valuation Standards Board was, perhaps, a bit more precise in their original definition of intangible assets[6]:

… assets that manifest themselves by their economic properties; they do not have physical substance; they grant rights and privileges to their owner; and usually generate income for their owner. Intangible assets can be categorized as arising from: Rights; Relationships; Grouped Intangibles; or Intellectual Property.The International Valuation Standards Committee goes on to define each of those categories. This was revised in March 2010 to[7]:

A non-monetary asset that manifests itself by its economic properties. It does not have physical substance but grants rights and economic benefits to its owner or the holder of an interest.Probably the briefest definition was provided by the Financial Accounting Standards Board (FASB)[8]:

… assets (not including financial assets) that lack physical substance.

According to the FASB, intangible assets are distinguished from goodwill. The FASB provides specific guidance for the identification of intangible assets such that any asset not so identified would fall into the catch-all category of goodwill.

Each of these definitions is correct and, in its venue, appropriate, but the nature of intangible assets requires more explanation. Some intangible assets are a subset of human capital, which is a collection of education, experience, and skill of a company’s employees. Structural capital is distinguished from human capital but also includes intangible assets such as process documentation and the organizational structure itself, which is the supportive infrastructure provided for human capital and encourages human capital to create and leverage its knowledge. Intangible assets are the codified physical descriptions of specific knowledge that can be owned and readily traded. Separability and transferability are fundamental prerequisites to the meaningful codification and measurement of intangible assets. Further, intangible assets receiving legal protection become intellectual property, which is generally categorized into five types: patents, copyrights, trade name (-marks and -dress), trade secrets, and know-how.

Why are intangible assets hard to measure?

Because one cannot see, or touch, or weigh intangibles, one cannot measure them directly but must instead rely on proxies, or indirect measures to say something about their impact on some other variable that can be measured.

Over the years, the FASB has sought to change the historical cost focus of measurement for management, accountants and auditors. In fact, the FASB has increasingly required fair value determinations, including intangible assets, as applicable to specific accounting standards thus adopted by both the Internal Revenue Service and the Securities and Exchange Commission.

The nature of intangible assets

Opportunity cost is a fundamental concept of finance and can be defined as the cost of something in terms of an opportunity foregone. Many finance courses focus on the opportunities available to utilize tangible assets, with the goal of applying those tangible assets to the opportunity with the highest return. Opportunities not selected can be viewed as returns foregone. The physical reality is that tangible assets can only be in one place at one time. Professor Baruch Lev looked at the physical, human, and financial assets (all considered tangible) as competing for the opportunity. In a sense, these assets are rival or scarce assets “… in which the scarcity is reflected by the cost of using the assets (the opportunity foregone).” [10]

Such assets distinguish themselves from intangible assets in that intangible assets do not rival each other for incremental returns. In fact, intangible assets can be applied to multiple uses for multiple returns. As Professor Lev says [11]:

The non-rivalry (or non-scarcity) attribute of intangibles – the ability to use such assets in simultaneous and repetitive applications without diminishing their usefulness – is a major value driver at the business enterprise level as well as at the national level. Whereas physical and financial assets can be leveraged to a limited degree only, by exploiting economies of scale or scope in production (e.g., a plant can be used for at most three shifts a day), the leveraging of intangibles to generate benefits – the scalability of these assets – is generally limited only by the size of the market. The usefulness of the ideas, knowledge, and research embedded in a new drug or a computer operating system is not limited by the decreasing returns to scale typical of physical assets (as production expands from two to three shifts, returns decrease due to the wage premium paid for third shift, employee fatigue, etc.).In contrast, intangibles are often characterized by increasing returns to scale. An investment in the development of a drug or a financial instrument (e.g., a risk-hedging mechanism), is often leveraged in the development of successor drugs and financial instruments. Information is cumulative, goes the saying.

Identification and classification of intangible assets

Identification of intangible assets is a broad endeavor. There are the well-accepted intangibles such as customer base, in-process research and development, and technology, and intellectual property intangibles such as patents, copyrights, trademarks, trade secrets, and know-how. The value of these assets typically account for most of an enterprise’s total intangible value, depending on the industry. There are also unique intangible assets peculiar to an industry or enterprise, such as bank deposits.

In an attempt to provide some structure to the recognition of identifiable intangible assets and to enhance the longevity of its financial model, the FASB classified intangibles into five categories[12]:

- Marketing-related intangible assets

- Customer-related intangible assets

- Artistic-related intangible assets

- Contract-based intangible assets

- Technology-based intangible assets

The measurement of intangible assets

The International Valuation Standards (IVS) Guidance Note No. 6, Business Valuation, addresses factors to be considered in valuing intangible assets. Further, in its delineation of applicable methodology, IVS Guidance Note No. 6 provides the basic economic approaches (the cost approach, the income approach, and the market approach) to valuing intangible assets.[14]

A key fundamental underlying the valuation of intangible assets is the concept of the tension between risk and return. As Professor Lev states [15]:

Assuredly, all investments and assets are risky in an uncertain business environment. Yet, the riskiness of intangibles is, in general, substantially higher than that of physical and even financial assets. For one, the prospects of a total loss common to many innovative activities, such as a new drug development or an internet initiative are very rare for physical or financial assets. Even highly risky physical projects, such as commercial property, rarely end up as a loss.

A comparative study of the uncertainty associated with R&D and that of property, plant, and equipment confirms the large risk differentials: the earnings volatility (a measurement of risk) associated with R&D is, on average, three times larger than the earnings volatility associated with physical investment.

The multiperiod excess earnings method

Major intangible assets for which it is possible to isolate discrete income streams are often valued using the Income Approach-Multiperiod Excess Earnings Method (MPEEM). This method honors the concept that the fair value of an identifiable intangible asset is equal to the present value of the net cash flows attributable to that asset, and recognizes the notion that the net cash flows attributable to the subject asset must recognize the support of many other assets, tangible and intangible, which contribute to the realization of the cash flows.

The MPEEM measures the present value of the future earnings to be generated during the remaining lives of the subject assets. Using the enterprise (100%) value of the business (the Business Enterprise Value or BEV) as a starting point, pretax cash flows attributable to the acquired assets as of the valuation date are calculated. The discount rates shown here are for illustrative purposes only and represent general relationships among assets. Actual rates must be selected based on consideration of the facts and circumstances related to each category of asset as determined based on market participants. A fundamental tenet of economics holds that return requirements increase as risk increases, with many intangible assets being inherently more risky than tangible assets. It is reasonable to conclude that the returns expected on many intangible assets typically will be at or above the average rate of return (discount rate) for the company as a whole. Note, however, that the returns expected on some intangible assets may be below the company average for a service business that has mostly intangible assets. The relationship of the amount of return, the rate of return (including risk), and the value of the asset creates a mathematical relationship previously discussed.

Contributory charges (CAC – returns on and off)

In applying the MPEEM to an intangible asset, after-tax cash flows attributable to the intangible are charged amounts representing a “return on” and, in some cases, a “return of” these contributory assets. The return on the asset refers to a hypothetical assumption whereby the project pays the owner of the contributory assets a fair return on the fair value of the hypothetically rented assets (in other words, return on is the payment for using the asset – an economic rent). For self-developed assets (such as assembled workforce or customer base), the annual cost to replace such assets should be factored into cash flow projections as part of the operating cost structure (e.g., sales and marketing expenses would serve as a proxy for a return of customer relationships). Similarly, the return of fixed assets is included in the cost structure as depreciation, which effectively acts as a surrogate for a replacement charge.

Together returns on and of, or contributory charges, represent charges for the use of contributory assets employed to support the subject assets and help generate revenue. The cash flows from the subject assets must support charges for replacement of assets employed, tangible or intangible, and provide a fair return to the owners of capital. The respective rates of return, while subjective, are directly related to the analyst’s assessment of the risk inherent in each asset. Generally, it is presumed that the return of the asset (reflecting the “using up” of the asset) is reflected in the operating costs when applicable (e.g., depreciation expense). The contributory asset charge is the product of the tangible or intangible asset’s value and the required rate of return on that asset.

An illustrative example of the relationship of intangible asset returns follows.

The CAC Guide describes returns on and of [16]:

A fundamental attribute of the MPEEM and of CAC calculations relates to a basic principle of financial theory known as Return on Investment (“ROI”). From the perspective of an investment in contributory assets, an owner of such assets would require an appropriate ROI. The ROI, in turn, consists of a pure investment return (what is referred to herein as return on) and a recoupment of the original investment amount (what is referred to herein as return of). Thus the most basic underpinning of CAC calculations is that contributory assets should earn a fair ROI.

The distinguishing characteristic of a contributory asset is that it is not the subject income generating asset itself; rather it is an asset that is required to support the subject income-generating asset. The CAC represents the charge that is required to compensate for an investment in a contributory asset, giving consideration to rates of return required by market participants investing in such assets.

The CAC is calculated based on the fair value of the contributory asset. Simply stated, it represents the fair value of a contributory asset multiplied by a required rate of return on, and in some cases of, that contributory asset.

It is important to note that the assumed fair value of the contributory asset is not necessarily static over time. Working capital and tangible assets may fluctuate throughout the forecast period, and returns are typically taken on estimated average balances in each year. Average balances of tangible assets subject to accelerated depreciation may decline as the depreciation outstrips capital expenditures in the early years of the forecast. While the carrying value of amortizable intangible assets declines over time, there is a presumption that such assets are replenished each year, so the contributory charge usually takes the form of a fixed charge each year. An exception to this rule is a noncompete agreement, which is not replenished and does not function as a supporting asset past its expiration period.

The following table provides examples of assets typically treated as contributory assets, and suggested bases for determining the fair return[17].

| Asset | Basis of Charge |

|---|---|

| Working capital | Short-term lending rates for market participants (e.g., working capital lines or short-term revolver rates) |

| Fixed assets (e.g., property, plant, and equipment) | Financing rate for similar assets for market participants (e.g., terms offered by vendor financing), or rates implied by operating leases, capital leases, or both, typically segregated between returns of (i.e., recapture of investment) and returns on |

| Workforce (which is not recognized separately from goodwill), customer lists, trademarks, and trade names | Weighted average cost of capital (WACC) for young, single-product companies (may be lower than discount rate applicable to a particular project) |

| Patents | WACC for young, single-product companies (may be lower than discount rate applicable to a particular project). In cases where risk of realizing economic value of patent is close to or the same as risk of realizing a project, rates would be equivalent to that of the project. |

| Other intangibles, including base (or core) technology | Rates appropriate to the risk of the subject intangible. When market evidence is available, it should be used. In other cases, rates should be consistent with the relative risk of other assets in the analysis and should be higher for riskier assets. |

Weighted average return on assets

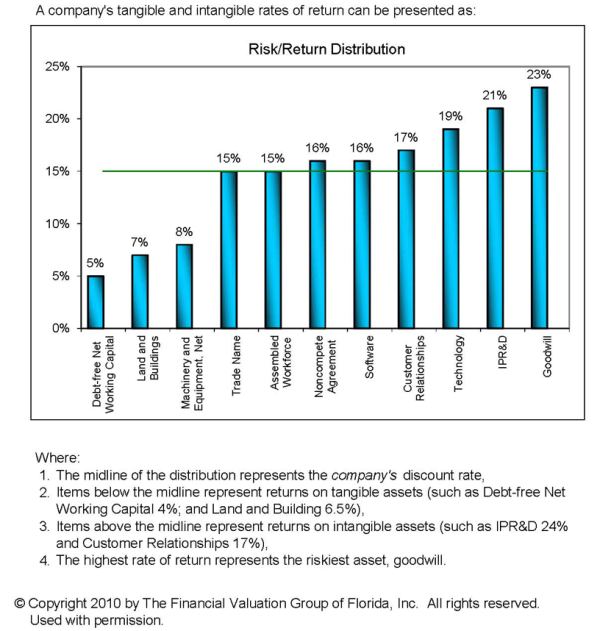

In the summary of values presented in the above graph, the valuation conclusions are separated into the following groups: elements of net working capital; property, plant, and equipment; intangible assets; and goodwill. Individual asset valuations are presented within each group.

In addition to presenting the summary of values, this graph provides a sanity check in the form of a weighted return calculation. The weighted average return on assets (WARA) calculation employs the rate of return for each asset weighted according to its fair value relative to the whole. The WARA should approximate the overall weighted average cost of capital (see Appendix) for the business. The analyst should take care and not rely blindly on the results of this exercise.

The returns for each asset are those actually used in the foregoing valuation methodology (i.e., for tangible assets and contributory intangible assets). For contributory intangible assets that were valued using a form of the income approach (trade name and noncompete agreement), the return is equal to the discount rate used to value that asset. Finally, the return for the assets valued under the excess earnings method is also their discount rate.

It should be clear that the one asset that does not have a return is goodwill, and, admittedly, the return assigned is determined by trial and error. Essentially, the goodwill return is imputed based on determination of the overall weighted return needed to equal the WACC. By its nature, goodwill is the riskiest asset of the group, and therefore should require a return much higher than the overall business return. Thus, in this calculation, the goodwill return of 23% suggests that goodwill is substantially riskier than all of the other assets, but, at a return of 23%, it is still well within reason for a proven going concern. Thus, we are satisfied that the returns chosen for each asset are reasonable

Fair market value

Fair market value is defined in the International Glossary of Business Valuation Terms issued by the American Institute of Certified Public Accountants, the American Society of Appraisers, the Canadian Institute of Chartered Business Valuators, the Institute of Business Appraisers and the National Association of Certified Valuation Analysts as[18]:

The price, expressed in terms of cash equivalents, at which property would change hands between a hypothetical willing and able buyer and a hypothetical willing and able seller, acting at arms length in an open and unrestricted market, when neither is under compulsion to buy or sell and when both have reasonable knowledge of the relevant facts.

The Uniform Standards of Professional Appraisal Practice definition of market value is the most probable price that a property should bring in a competitive and open market under all conditions requisite to a fair sale, the buyer and seller, each acting prudently, knowledgeably and assuming the price is not affected by undue stimulus. The USPAP definitions state[19]:

MARKET VALUE: a type of value, stated as an opinion, that presumes the transfer of a property (i.e., a right of ownership or a bundle of such rights), as of a certain date, under specific conditions set forth in the definition of the term identified by the appraiser as applicable in an appraisal.

Comment: Forming an opinion of market value is the purpose of many real property appraisal assignments, particularly when the client’s intended use includes more than one intended user. The conditions included in market value definitions establish market perspectives for development of the opinion. These conditions may vary from definition to definition but generally fall into three categories:

- the relationship, knowledge, and motivation of the parties (i.e., seller and buyer);

- the terms of sale (e.g., cash, cash equivalent, or other terms); and

- the conditions of sale (e.g., exposure in a competitive market for a reasonable time prior to sale).

Fair value under the Financial Accounting Standards Board ASC 820 is[20]:

the price paid that would be received to sell an asset or paid to transfer a liability in an orderly transaction between market participants at the measurement date.

Fair value allows an in-use premise, is an exit price notion extracted from market participants in a principal or most advantageous market for a defined unit of account. Normally, when valuators or preparers are developing the FV work product, we intangible appraisers will ask real estate appraisers for the “value” of land and building. They in turn scope to FMV and specifically a direct to asset (stand alone) in-exchange premise driven by market comparables as adjusted subjectively with returns independent from and not correlated with returns on or of all other assets.

While there are nuanced differences among these definitions, they are by and large consistent. What is important for this article is that we believe a consistent hypothetical investor is prevalent in each definition. Further, while we recognize the differences in the two premises of value, value in use and value in exchange, we believe the hypothetical investor standard does not change. If you, the reader agree, then:

| Vie | = | Iie | = | RP |

| rie |

Where:

- Vie is value in exchange

- Iie is the dollar income for the subject property

- rie is the rate of return for the subject property in exchange and

- RP is the subject property

Further:

| Viu | = | Iiu | = | RP |

| riu |

Where:

- Vie is value in use

- Iie is the dollar income for the subject property

- rie is the rate of return for the subject property in use and

- RP is the subject property

And:

RP = BEV – TA1 – TA2 – TA3… – IA1 – IA2 – IA3…

Where:

- RP is the subject property

- BEV is the Business Enterprise Value

- TA1, TA2, and TA3… are the individual tangible assets and

- IA1, IA2, and IA3… are the individual intangible assets

Then assuming the consistent hypothetical investor standard:

| RP = Vie = | Iie | = Viu = | Iiu | = BEV – TA1 – TA2 – TA3… – IA1 – IA2 – IA3… |

| rie | riu |

Our conclusion is based upon the consistent hypothetical investor standard the subject real property should be the same value regardless of whether the value in exchange or value in use premise is used as long as the business enterprise value is properly valued with all assets, tangible and intangible, separately valued and allocated.

Use of a specialist

This stuff is hard. It’s hard for several reasons, not the least of which is two disciplines crossing paths. The real estate appraiser’s and the business appraiser’s jargon uses the same words with different meanings and different contexts. Regardless of whether the lead appraiser is real estate or business, the lead must now consider retaining assistance with a qualified (skill, education and experience) counterpart. Certainly in the world of financial reporting, auditors must now consider a knowledgeable real estate appraiser. Specifically :

The market for valuation-related services in financial reporting is seen as a potential growth area for real estate valuers, working with (or for) accountants, business valuers, and personal property appraisers. As a significant example, corporate assets often must be valued for inclusion on corporate financial statements. A corporate merger or acquisition also triggers a valuation of the entire business, requiring that allocations be made for tangible and intangible assets in addition to determining if there is any residual goodwill in the business value…

In valuation for financial reporting assignments, a valuer may be recognized as what auditing standards consider a specialist. The American Institute of Certified Public Accountants defines a specialist as “a person (or firm) possessing special skill or knowledge in a particular field other than accounting of auditing,” according to AICPA Statement on Auditing Standards No. 73: Using the Work of a Specialist. In this context, an appraiser has the valuation knowledge and expertise that auditors are neither required nor expected to have, such as specialized knowledge of professional valuation standards, relevant state laws and regulations, property characteristics and utility, trends in market conditions, and analysis of the highest and best use of real property. However, auditors generally are expected to be able to use the audit evidence provided by a valuation specialist.

Citations

- The authors gratefully acknowledge John Wiley & Sons, Inc. and its cooperation granting permission for some original work used as a basis for this article, especially from the author’s Valuation for Financial Reporting, 2002, 2007 and 2010. All work used with permission. This article represents original work by the authors.

- https://www.sec.gov

- https://finance.yahoo.com/news/disney-fox-deal-change-media-151103603.html

- The Appraisal of Real Estate, 14th Edition, © 2013, Appraisal Institute • 200 W. Madison • Suite 1500 • Chicago, IL 60606 • www.appraisalinstitute.org, page 492, Chapters 23, 24 and other

- Margaret Blair and Steven Wallman, Unseen Wealth: Report of the Brookings Task Force on Intangibles (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2001), p. 3.

- International Valuation Standards Council, Guidance Note No. 4, Valuation of Intangible Assets (2006), at 3.15.

- International Valuation Standards Council, Guidance Note No. 4, Valuation of Intangible Assets (2010), at 2.3.

- Financial Accounting Standards Board, Accounting Standards Codification (2009), Glossary.

- Margaret Blair and Steven Wallman, Unseen Wealth: Report of the Brookings Task Force on Intangibles (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2001), p. 15.

- Baruch Lev, Intangibles: Management, Measurement and Reporting (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2001),p.22.

- Ibid., p. 23.

- Financial Accounting Standards Board, Accounting Standards Codification (2009), at 805-20-55-13.

- International Valuation Guidance Note No. 6, Business Valuation (2000, revised 2005), at 5.10.7.

- Ibid., at 5.14.

- Baruch Lev, Intangibles: Management, Measurement and Reporting (Washington, DC: Brookings Institution Press, 2001), p.39.

- The Appraisal Foundation, Best Practices for Valuation in Financial Reporting, The Identification of Contributory Assets and the Calculation of Economic Rents, Exposure Draft, February 25, 2009, at 1.5-1.7.

- Ibid.

- https://www.aicpa.org (glossary link)

- http://alappraisal.com/uspap/Definitions.pdf

- https://asc.fasb.org (section link)

- Op. Cit. The Appraisal of Real Estate, 14th ed. p. 695-696

Related Posts

- Valuation for Financial Reporting: Fair Value, Business Combinations, Intangible Assets, Goodwill, and Impairment Analysis

by Michael J. Mard, James R. Hitchner, and Steven D. HydenMichael Mard and co-authors have…

- The Role of Property Tax in American Government (Part 2)

By Todd D. Jones, MAI, CRE, FRICS and Michael J. Mard, CPA/ABV, CPCU Note to…